Nobody likes it when the other party to a confidential settlement communication spills the beans in public. Like they say, snitches get stitches.

Lawyers try to avoid this problem by putting something like this at the top of their letters and emails about settlement:

*CONFIDENTIAL SETTLEMENT COMMUNICATION SUBJECT TO FRE 408*

Why do lawyers do this?

The answer is that if you put this at the top of your email or letter, then the party who receives it is not allowed to use your statements against you for any purpose. This is federal law.

I’m just kidding. That’s not what the law is. Cue the “Bad Legal Takes” account on Twitter.

But there are some common misconceptions about the settlement communications rule, even among lawyers.

Before I get to those, let’s take a look at the rule itself.

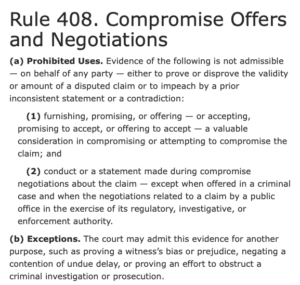

Federal Rule of Evidence 408 says this:

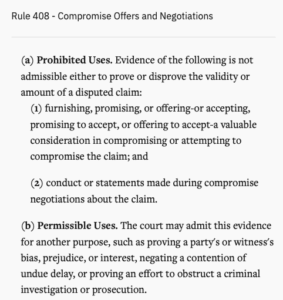

Most states have a similar rule. Texas, where I practice, has its own version of Rule 408, which is similar to—but not identical to—the Federal Rule:

For simplicity, let’s put aside for now the part of the federal rule about certain criminal cases. We can then see, based on the text alone, that both the Texas rule and the federal rule make a statement inadmissible if:

(1) there is a “disputed claim”

(2) the statement is “made during compromise negotiations about the claim”

(3) the statement is offered for the purpose of proving or disproving “the validity or amount of a disputed claim.”

The “exceptions” in part (b) are not exceptions per se; they really just clarify that the rule does not bar admission of a settlement communication offered for some other purpose.

Seems simple enough, but what does this really mean, and why do we have this rule?

Let’s take a very basic example. Suppose you get in a car accident with Dave Driver and there’s a lawsuit. During a discussion of settling the case, Dave says “ok, I ran the red light, but the damages you’re asking for are just too much.”

Under Rule 408, you can’t offer Dave’s statement “I ran the red light” as evidence in court. As the federal version of the rule makes clear, you can’t even offer the statement as impeachment evidence if Dave testifies in court “that light was green.”

At first, this doesn’t seem fair. How can Dave get away with admitting he ran the red light and then say the opposite in court?

But if you think about it, if you could use Dave’s statement against him in court, his lawyer might never let Dave say a word in settlement discussions. Why chance it?

No, we want to encourage people to speak candidly and freely in settlement negotiations. We don’t want them to think anything they say can and will be used against them. That would have a “chilling effect” on attempts to compromise disputed claims. That’s why we have Rule 408.

On the other hand, we don’t want people to use the rule to block admission of evidence that is relevant for some other purpose. Suppose Dave’s insurance company offers Pam Passenger money in exchange for an agreement not to testify that Dave ran the red light. Part (b) of the rule clarifies that evidence offered for some other relevant purpose—such as showing Pam’s bias—could still be admissible.

And keep in mind, the statement has to be part of a communication about a compromise. A statement that simply asserts a party’s position or makes a demand may not be a “compromise” communication.

Now that we understand the elements of the rule and its purpose, let’s look at some common misconceptions about the rule.

This one seems pretty obvious, but some lawyers still seem to think that if they put this kind of label at the top of a letter, the letter can never be offered as evidence. Some will even get bent out of shape and accuse you of being unprofessional if you try.

Whether this is unprofessional will of course depend on the circumstances, but of course, just because one lawyer labeled something a Rule 408 communication does not make it inadmissible. If you’re going to object to the admission of the statement in the courtroom, you will still have to meet each of the elements I outlined earlier.

On the other hand, putting the “Rule 408” label on your letter isn’t a total waste of time. It does at least provide some evidence that at least one party intended the communication as a “statement made during compromise negotiations about the claim,” and that doesn’t hurt.

Conversely, leaving out the Rule 408 label does not mean that Rule 408 does not apply, but again, it probably doesn’t hurt to use the label—if you’re concerned about the communication being used against your client later in court.

This one also seems fairly obvious if you read the rule. But it’s not uncommon for lawyers to object to any evidence of a statement made during a settlement negotiation, even when the evidence is offered for some other purpose. And if the judge doesn’t grasp the distinction, the objection may even be sustained.

But still, lawyers should not think that the rule will keep out evidence of settlement communications, regardless of the purpose. Several times in preparing for a trial I have pulled case law applying Rule 408 to support or respond to an anticipated objection, and I can tell you that most of the cases you run across say that Rule 408 did not bar admission of the evidence, because the evidence was offered for some other purpose.

This is really a corollary to misconception no. 2. If a party’s settlement communication itself is evidence of commission of a crime, then Rule 408 would not bar offering that communication for the “other purpose” of proving that the party committed a crime.

Suppose a mob boss is a party to a contentious civil lawsuit about a restaurant lease. During a conference call to discuss settlement, he says “this is really a reasonable offer, and if you don’t take it, bad things could happen to your nice restaurant.”

In that case, Rule 408 would not prevent the government from offering the mob boss’s statement as evidence in a prosecution for extortion. The statement would meet the first two elements of Rule 408—it was made during compromise negotiations of a disputed claim—but it would not be offered for the purpose of proving or disproving the validity or amount of a disputed claim. Rather, the evidence would be offered for the purpose of proving that the mob boss committed a crime by making the statement.

This is a somewhat subtle distinction, especially for non-lawyers, but it’s an important one.

Rule 408 on its face talks about whether evidence is “admissible.” It doesn’t say that the evidence is “privileged.”

This is an important distinction. To illustrate, let’s consider the attorney-client privilege rule in contrast. That rule governs both admissibility and privilege. If I have a confidential communication with my lawyer for the purpose of obtaining legal advice, that communication is generally privileged.

Privileged means both that I can’t be required to disclose the communication in a lawsuit, and that the opposing party cannot offer the statement as evidence in court.

Rule 408 doesn’t work like that. It says nothing about making the statement privileged from disclosure. Generally, if a settlement communication is relevant to disputed issue in a lawsuit, then Rule 408 doesn’t prevent a party to the lawsuit from demanding disclosure of the communication, such as in a pretrial deposition or in a request for production of documents.

So, while I can object to the opposing party attempting to offer the settlement communication as evidence, that doesn’t mean the statement is exempt from disclosure.

This one is similar to no. 4. Rule 408 is a rule of admissibility, not a rule of confidentiality. The rule says nothing about disclosing an opposing party’s settlement communication to a third party, or to the general public.

So if Dave Driver says “I ran the red light” during a settlement discussion, there is nothing to stop the other party from going to the press and saying “Driver admitted he ran the red light!”

That is, unless the parties agreed to keep the settlement communications confidential. But that would be a contract law issue, not a Rule 408 issue. Dave would have to prove the existence of an agreement to keep the settlement communications, a breach of the agreement, and damages resulting from the breach. Of course, in some cases there could be public policy issues with enforcement of the agreement.

This leads to my settlement communication practice tips for lawyers:

1. If you’re concerned about sensitive statements your client might make during a settlement negotiation, consider entering into a written agreement up front providing that both sides will keep the settlement communications confidential and not offer them as evidence for any purpose. (This would be broader than Rule 408.)

2. Understand that, as a practical matter, your client’s only recourse in the event of public disclosure will be a claim for damages, which will probably be difficult to prove and won’t really undo the reputational damage.

3. Suggest your client try to avoid making any statements that could be considered a crime.

Like they say, don’t do the crime if you can’t do the time.

Zach Wolfe (zach@zachwolfelaw.com) is a Texas trial lawyer who handles non-compete and trade secret litigation at Zach Wolfe Law Firm (zachwolfelaw.com). Thomson Reuters named him a Texas “Super Lawyer”® for Business Litigation in 2020, 2021, and 2022. He hereby designates this entire blog post confidential under FRE 408.

These are his opinions, not the opinions of his firm or clients, so don’t cite part of this post against him in an actual case. Every case is different, so don’t rely on this post as legal advice for your case.