Abraham Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address is one of the most famous, most quoted, and most recited speeches of all time. It is also one of the shortest among its peers at just 10 sentences.

In this article, we examine five key lessons which you can learn from Lincoln’s speech and apply to your own speeches.

This is the latest in a series of speech critiques here on Six Minutes.

I encourage you to:

When trying to persuade your audience, one of the strongest techniques you can use is to anchor your arguments to statements which your audience believes in. Lincoln does this twice in his first sentence:

Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth on this continent a new nation, conceived in liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal. [1]

Among the beliefs which his audience held, perhaps none were stronger than those put forth in the Bible and Declaration of Independence. Lincoln knew this, of course, and included references to both of these documents.

The days of our years are threescore years and ten…

(Note: a “score” equals 20 years. So, the verse is stating that a human life is about 70 years.)

Therefore, Lincoln’s “Four score and seven years ago” was a Biblically evocative way of tracing backwards eighty-seven years to the signing of the Declaration of Independence in 1776. That document contains the following famous line:

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights, that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.

By referencing both the Bible and the Declaration of Independence, Lincoln is signalling that if his audience trusts the words in those documents (they did!), then they should trust his words as well.

How can you use this lesson? When trying to persuade your audience, seek out principles on which you agree and beliefs which you share. Anchor your arguments from that solid foundation.

To learn more about the speaking skill of Abraham Lincoln, check out Speak Like Churchill, Stand Like Lincoln (read the Six Minutes review).

Lincoln employed simple techniques which transformed his words from bland to poetic. Two which we’ll look at here are triads and contrast.

First, he uttered two of the most famous triads ever spoken:

How can you use this lesson? While the stately prose of Lincoln’s day may not be appropriate for your next speech, there is still much to be gained from weaving rhetorical devices into your speech. A few well-crafted phrases often serve as memorable sound bites, giving your words an extended life.

“ When trying to persuade your audience, seek out principles on which you agree and beliefs which you share. Anchor your arguments from that solid foundation. ”

In the first lesson, we’ve seen how words can be used to anchor arguments by referencing widely held beliefs.

In the second lesson, we’ve seen how words can be strung together to craft rhetorical devices.

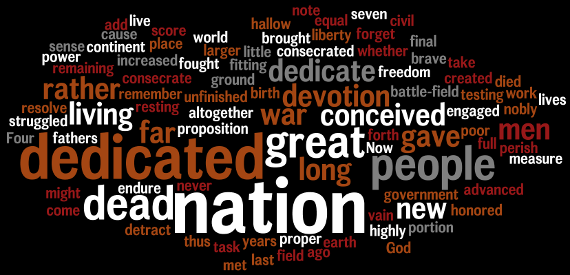

Now, we’ll turn our attention to the importance of repeating individual words. A word-by-word analysis of the Gettysburg Address reveals the following words are repeated:

While this may not seem like much, remember that his entire speech was only 271 words.

By repetitive use of these words, he drills his central point home: Like the men who died here, we must dedicate ourselves to save our nation.

How can you use this lesson? Determine the words which most clearly capture your central argument. Repeat them throughout your speech, particularly in your conclusion and in conjunction with other rhetorical devices. Use these words in your marketing materials, speech title, speech introduction, and slides as well. Doing so will make it more likely that your audience will [a] “get” your message and [b] remember it.

More examples of three part speech outlines are described in Why Successful Speech Outlines follow the Rule of Three.

The Gettysburg Address employs a simple and straightforward three part speech outline: past, present, future.

How can you use this lesson? When organizing your content, one of the best approaches is one of the simplest. Go chronological.

The final sentences of the Gettysburg Address are a rallying cry for Lincoln’s audience. Although the occasion of the gathering is to dedicate a war memorial (a purpose to which Lincoln devotes many words in the body of his speech), that is not Lincoln’s full purpose. He calls his audience to “be dedicated here to the unfinished work” [8], to not let those who died to “have died in vain” [10]. He implores them to remain committed to the ideals set forth by the nation’s founding fathers.

How can you use this lesson? The hallmark of a persuasive speech is a clear call-to-action. Don’t hint at what you want your audience to do. Don’t imply. Don’t suggest. Clearly state the actions that, if taken, will lead your audience to success and prosperity.

[1] Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth on this continent a new nation, conceived in liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.

[2] Now we are engaged in a great civil war, testing whether that nation, or any nation, so conceived and so dedicated, can long endure.

[3] We are met on a great battle-field of that war.

[4] We have come to dedicate a portion of that field, as a final resting place for those who here gave their lives that that nation might live.

[5] It is altogether fitting and proper that we should do this.

[6] But, in a larger sense, we can not dedicate, we can not consecrate, we can not hallow this ground.

[7] The brave men, living and dead, who struggled here, have consecrated it, far above our poor power to add or detract.

[8] The world will little note, nor long remember what we say here, but it can never forget what they did here.

[9] It is for us the living, rather, to be dedicated here to the unfinished work which they who fought here have thus far so nobly advanced.

[10] It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us—that from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion—that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain—that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom—and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.

For further reading, you may enjoy these excellent analyses:

This article is one of a series of speech critiques of inspiring speakers featured on Six Minutes.

Subscribe to Six Minutes for free to receive future speech critiques.

Andrew Dlugan is the editor and founder of Six Minutes. He teaches courses, leads seminars, coaches speakers, and strives to avoid Suicide by PowerPoint. He is an award-winning public speaker and speech evaluator. Andrew is a father and husband who resides in British Columbia, Canada.